Producer/Gehry[UCRC]+Ting WANG[HKU]

Text/Gehry[UCRC] + Yating SONG[UCRC] + chen CHEN

Translation/Yating SONG[UCRC]

When people started to see nature in the city as a more complex idea than Frederick Law Olmsted’s ‘picturesque’ landscape, urban parks has become less representational and more functional, creating socio-economic, cultural and ecological values. Regarded as a form of ‘quasi-public goods’, urban parks in China has entered a dilemma that its current management models couldn’t resolve: neither fully state-owned parks or privately-run parks are balancing well between public interest and profitability. The majority of Chinese urban parks are managed by the state in the public sector, under the jurisdiction of the Landscape Bureau, the City Appearance Administrative Bureau, or other associated departments. Their design, management, procurement, maintenance, and renewal are also the responsibility of these departments or their designated enterprises. Social institutions and individuals are normally not able to participate. The users of the parks not only have no rights over the parks’ spatial organisation and landscape design, but also subject to many unnecessary or unsuitable rules regarding safety or the use of the space. These have led to numerous common problems such as low spatial efficiency, facility damage and outdated designs. This management model that puts a single body in charge also generates huge pressure to bridge the demand-supply gap of urban parks. Hence, new management models are widely sought after among governments, enterprises and individual practitioners.

In Wuhan, The Landscape and Forestry Bureau, in collaboration with Changjiang Daily and the neighbourhood committee, explores a new model for governments and third-party organisations to jointly manage urban parks, using Jiefang Park in Wuhan as a pilot study. The project revitalises the neighbourhood by restructuring the function of the park and catalysing interaction between different visitor groups.

On the other side in Shanghai, as of December 2019, the total number of registered urban parks has reached 352, increasing 135 since 2017, and far surpassing the initial target of 300. Shanghai’s endeavour in building parks revolves around keywords such as ‘public space’, ‘urban regeneration’, ‘city competitiveness’, ‘lifestyle’ and so forth. On such basis, an innovative park management model in which a third party participates in the park’s construction and operation has become the ideal choice, in terms of attracting social funds and accelerating construction. Xuhui Vanke Center Green Spine Park, which aims to become ‘Shanghai's largest CBD central park’ is a practice under such a new model. Its development process, however, is not without its challenges. The biggest issue is not funding, but the irreconcilable contradictions between property rights, management rights, and usage rights, due to the outdated organisation system.

By studying these two public-private partnerships cases in Wuhan and Shanghai, we hope to gain further insights into certain trends in the construction and management of urban parks in China.

WUHAN

Multi-Organisational Partnership: Managing Conventional Urban Parks

Jiefang Park is located in the northeast of Hankou, Wuhan, formerly a racecourse of foreign merchants in the colonial period. After liberation, the government retrieved 132 acres of land and converted it into a park. In 2005, after redesigned by Canadian landscape architecture office WAA, the park became a comprehensive park with the largest green area, as well as the biggest ecological park in Wuhan. It was hence known as the ‘urban green lung’. The 10 hectares of waterscape in the park was designed to circulate and self-purify. The park has since start to offer free access for the public. Yet, it was far from being completely public and open by only removing walls and gates.

Aerial view of Wuhan Jiefang Park.(Source/Changjiang Daily)

At the beginning of 2018, a new renovation plan was proposed to transform the park’s leftover spaces into participative and interactive open spaces under the concept of ‘shared space for better life’. Indoor space that was previously a 560-square-metre bonsai garden within Jiefang Park, was thus converted into a multifunctional venue to provide space for the park's free public activities, including a gallery, a large classroom, the home of the civic garden director, and an ecological ‘flower nest’. The gallery cooperates with major universities in Wuhan to provide a platform for students to make and display art works; the classroom focuses on the park’s long-established natural education services for children; the home of the civic garden director is a place for public communication and consultation under the 2014-established ‘civic garden director’ management system; the ‘flower nest’ is an ecological gardening workshop for families. The building of ‘shared space for better life’ is considered another attempt after the establishment of the ‘civic garden director’ system in Wuhan.

Before renovation into a park art gallery, the original space was a vacant house in the park.(Source/Changjiang Daily)

After the renovation, the Park Art Museum is free to the public, and undertakes exhibitions such as calligraphy and painting and other cultural works.(Source/Changjiang Daily)

Interaction as Key to Transform Conventional Urban Parks

Although conventional urban parks are important green spaces for Chinese cities, the services they provide are relatively simple, other than offering the landscape itself. However, economic growth and the improvement of urban living conditions leads to a higher demand for more diverse soft infrastructures among urban residents, other than just hard infrastructures to accommodate their cultural life. Therefore, through renovating Jiefang Park, the Wuhan Landscape and Forestry Bureau (hereinafter referred to as ‘WLFB’) hopes to reshape the spatial and functional structure of the park and to provide services for all age groups. Specifically, the main strategy is to redesign leftover or inefficient spaces to match the real needs of park users.

On another note, the area of urban greenspace has always been an important figure to evaluate a city’s greenspace provision, however, in the design of green spaces, too much attention has been paid to the ecological quality of the physical space, while its functionality and accessibility was largely ignored. In recent years, when the idea of ‘participatory urban planning’ gains more public attention, urban parks, as public spaces or ‘quasi-public goods’ of the city, also seek more public participation in their design and management. Public participation has three characteristics: fundamental, spontaneous, and social. Evidently, the social character of Jiefang Park is relatively weak at present. The park’s visitors are mostly the elderly and children, and activities within the park are usually small-scaled and between family members. In another word, the social network of the park is scattered in small groups.

The all-age-friendly city salon pictured. WLFB proposed that the park should be an open platform where people of all ages can find a way to interact and communicate with each other. This has also become the central concept of Jiefang Park’s transformation, which was later articulated into ‘shared space for better life’.(Source/Changjiang Daily)

Compared to a community park that is relatively autonomous in terms of management, a comprehensive urban park follows a management system that has been long established. There are certain difficulties for Jiefang Park to transform its social network that is scattered and isolated into one that is highly interactive between local communities. In reality, as urban public spaces including squares are often overly occupied by seniors and middle-aged people, they are stereotyped to be unattractive and unfashionable by many young people. As this phenomenon underlines the lack of mutual understanding, it is very necessary to create a space for face-to-face communication and interaction. This would first require a sharing system to be established. For this purpose, WLFB firstly cancelled the regulations on the park’s activity types in order to meet the needs of different age groups. Secondly, WLFB and Changjiang Daily formed a special team called ‘Wuhan Parkers’ to offer planning, design and management services for public events in the park or community spaces nearby.

From 2014 to 2017, ‘Park Classroom’has hold 384 nature education classes for Wuhan’s families. Receiving wide praise, a further series of the classes called the ‘florist’s classroom’ was launched, in which ten of the park’s gardeners and engineers with rich planting experience and theoretical knowledge were selected to work with elementary students. In these workshops, each instructor taught a group of three the growth habit of plants around a practical gardening problem though both in-site and online tutoring.(Source/Changjiang Daily)

Besides serving in the community scale, Jiefang Park also pays attention to its role in the urban scale. As Wuhan is known to be a city with numerous universities – as much as 91 universities and colleges, the park specifically set up the ‘park gallery’ for students. The team ‘Drawing China in Calligraphy’ from the School of Art and Design of Wuhan Technology and Business University was the first to display their work series ‘Drawing Wuhan in Calligraphy’, and also design products in the gallery.(Source/Changjiang Daily)

When making overall plans and organising events, WLFB pays extra attention to the most popular interests of different groups of people, so that visitors of different ages, occupations, and with different hobbies can participate in these activities together. For example, Chinese New Year paper cutting, family gardening, reading club, and various sharing groups are events organised with such an idea. (Source/Changjiang Daily)

In terms of urban character, Wuhan is a dynamic city with strong creative power from college students. There is, however, not enough public space within the city to display and foster such creative power outside campus. Therefore, the gallery of Jiefang Park is an innovative programme that challenges the current condition Wuhan’s public space. Of course, this couldn’t be done without the support from various players. WLFB, Jiefang Park, as well as Changjiang Daily, have all provided start-up funds for the shared space.

As a mainstream local media in Wuhan, Changjiang Daily is familiar with the cultural and social needs of people in Wuhan, and has its own communicative power across different communities. Its local credibility also helps to eradicate isolation and reshape the social network. This is also a major drive for WLFB to collaborate with cultural institutions such as Changjiang Daily, instead of simply purchasing their services as a government would normally do.

Public-Private Partnership, A Precondition for Low-Cost Management

From the organisational perspective, while managing urban parks in an urban scale is a responsibility of the government, vitalising theses green space and making wise investments would require the participation of all interest parties. Throughout the development life cycle of a park project, which includes site selection, planning and design, construction and renovation, event organisation and management, the most difficult issue is how to think in the users’ perspectives.

For this reason, firstly, WLFB made efforts to integrate the public dimension into the park’s planning, design and management. The intention is to give its visitors the power of park management, other than only being a ‘user’. This has also been a reason why Wuhan established the ‘civic garden director’ system back in 2014.

The public election for the park gallery director was held to advocate public participation under the new management model. (Source/Changjiang Daily)

Besides recruiting management personnel, in terms of neighbourhood planning, WLFB also conducted a survey on the surrounding communities before the renovation to study their needs, under the general design framework of ‘investigation, site analysis, planning’. Through a series of symposiums with experts from Wuhan University, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, and Wuhan Technology and Business University, the design concept of ‘shared space for better life’ was conceived, into which the suggestions from other investors are also integrated. The management and maintenance of the park has also gradually become a testbed for public participation in later phases. In addition to consistent communication between users and investors, the refinement of the shared space also benefits from the communities who organise events and carry out maintenance, as well as the users’ continuous feedbacks which contributes to the spaces’ vitality and visibility.

In terms of the events, following the principle of ‘dual public welfare’, organisations can set up events free of charge in the ‘shared space for better life’. The park provided free venue for the events, and the institute provided a couple of free public activities in relation to the shared spaces’ programmes. Regarding activity types, besides collaborating with educational institutions, including primary and secondary schools, the park also cooperates with social clubs and groups.

The Wuhan Writers Association started a campaign called ‘Wuhan writers’ shared bookshelf’. In just two weeks, the shared space received more than 700 donated signed books. This not only gives writers more exposure of their works, but also provides the public with the opportunity to read for free.(Source/Changjiang Daily)

Shared Space for Better Life as A Conceptual Paradigm

‘Shared space for better life’ could potentially become a model, or a guiding concept, but never a standard for Wuhan’s public space. Through redefining the function of the space, it expands the scope of the space’s activities, diversifies the lifestyles of urban residents, and creates an open, dynamic and sharing community.

It is universal that urban dwellers need public space, but their needs differ, and therefore urban public space should show a certain degree of diversity. On the one hand, people of different cultural backgrounds have different ideologies for nature and the built environment. On the other hand, different parks may vary greatly in their site conditions and resources. Accordingly, the design concept of the shared space should be further developed and ‘localised’ to make use of its unique conditions.

In the case of Jiefang Park, park management also takes into account the feedback from a wide public for the ‘shared space for better life’. A general design guide with standards was composed upon these opinions and suggestions, and a ‘model space’ was constructed to showcase and further promote the concept. In the upcoming 2018, two or three more shared spaces will be built in Wuhan’s urban parks.

SHANGHAI

Green Spine Park: A Practice of Privately-Run Park

In 2012, led by Vanke Co., Ltd. (hereinafter referred to as ‘Vanke’), three companies jointly achieved development rights for the commercial plots in the CBD core area of Xuhui Midtown Integrated Development Area (hereinafter referred to as ‘Xuhui Midtown’). For a long time, Xuhui Midtown, located in the central area of Xuhui District, has not gained much attention except for its advantageous location. Compared with other development parcels, Xuhui Midtown lacks a clear functional positioning and competitive industries. In addition, with the development of Shanghai’s other transportation infrastructures, Shanghai South Station's role as the city’s transportation hub has weakened, and it is no longer an urban tissue strong enough to tie together the northern and southern areas of Xuhui. Consequently, by bringing in social capital from real estate enterprises and related cooperatives, this vacant plot adjacent to Shanghai South Station is looking for new opportunities.

Regional changes in Xuhui Midtown-Shanghai South Railway Station (2002, 2019, via Google Earth)

The Third Spone Alone Metro and Train

For this plot, building a park seems to be a straightforward solution out of its geographical condition, boarding the Humin Viaduct and on the ground surface of the metro line. Taking into account its long and narrow shape and spatial characters – especially orientated along the underground track – the design of the Xuhui Vanke Center Green Spine Park (hereinafter referred to as ‘Green Spine Park’) proposes an ‘unhindered’ and ‘oriented’ corridor to connect the surrounding public spaces. The sense of orientation is strengthened by lineal elements such as corridors and pedestrian bridges, which also stich up the spaces scattered by the main road.

The designer of the project concluded, to encourage people living and working nearby to enjoy this space at any time is an important consideration of the design. From the perspective of urban planning, the area needs a dense road network, but speaking from the use of open spaces, the roads become obstacles. The pedestrian flow become dispersed once the park and commercial buildings are separated.(Source/Xuhui Vanke Center)

To improve on physical connectivity, the pedestrian corridor forms the axis of Green Spine Park, where micro spaces and art interventions are arranged along to create multiple forms of connection between different functions of the surrounding area and the park. In addition to leisure space with greenery, cultural and art space have also been incorporated to increase diversity and make the corridor more enjoyable than a normal walkway. In the future, an exit of Metro Line 15 will be opened in the southwest corner of Green Spine Park. Walking through the park will become another option for pedestrians.

Park, Botanical Garden, or Public Activity Center

Compared with conventional parks, Green Spine Park values its role as a public space and strives to integrate contemporary urban life into its design. These various programmes on the one hand form a strong and diverse interaction with the surrounding commercial complexes, and on the other hand, become a hub for creative crowds in the area.

The park consists of a stepped plaza for outdoor performance, an art exhibition centre that can accommodate 500 people, and a botanical garden for nature education, which includes an aquatic garden and a medical herbs rock garden. (Source/Xuhui Vanke Center)

Various of plants along the green mid-town create a space that differs from traditonal urban garden scenery.(Source/Xuhui Vanke Center)

Regarding the botanical garden’s vegetation, the project manager of Green Spine Park added: ‘We’re introducing plants varieties from the Shanghai Chenshan Botanical Garden and inviting botanical experts for reviews. There will be nearly 350 types of plants in the education area in the future. The Shanghai Chenshan Botanical Garden is also responsible for the maintenance and management of these plants. This serves the 100,000 residents in the surrounding area in a way that viewing plant collection will no longer be a long trip.’ In fact, a significant trend could be observed, as more and more urban farms and suburban vegetable gardens emerge, that people are becoming more aware of nature’s influence on personal growth and the city’s sustainability. It is important to retrieve the balance between urban life and nature, in a way that the latter is not merely used as an ornament or an ecological tool of the former.

An art exhibition centre is another way to exploit the urban green. A park is a flexible space, full of possibilities in the form of voids instead of fixed volumes. ‘The highlight of Green Spine Park Art Centre is “green”, which is not a common feature of Shanghai’s art centres. Exhibitions and events from other art centres can be moved to Green Spine Park Art Centre for different effects.’ said the project manager of Green Spine Park.

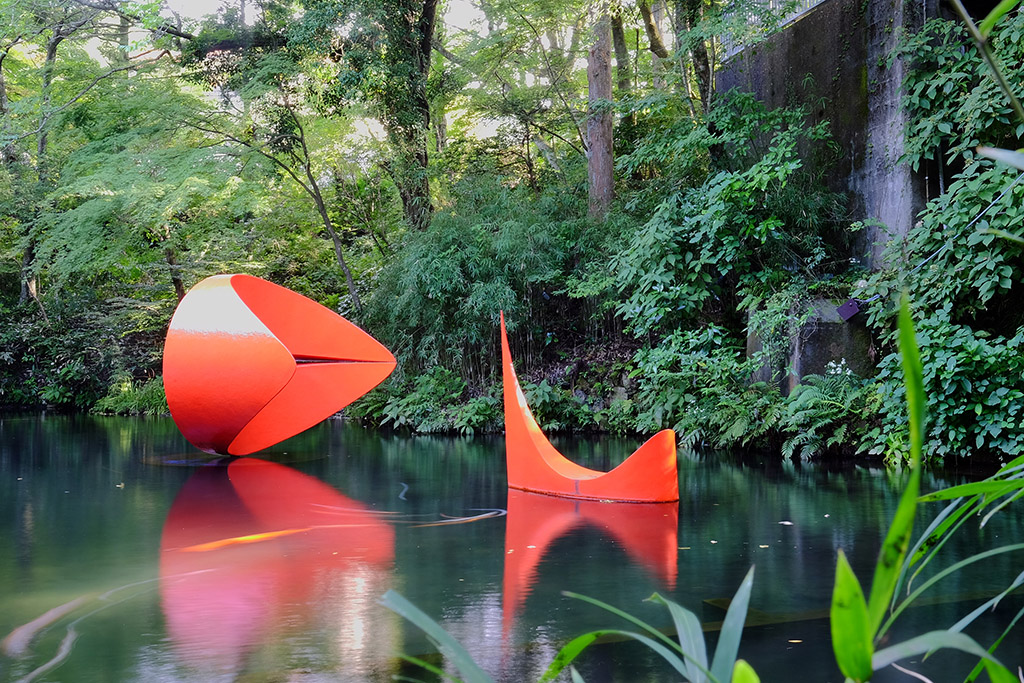

The Hakone Open-Air Museum in Japan. Most of the exhibits are displayed in the open air. With a touch of nature – greenery, weather, etc. – the sculptures could display a more refined and glorious texture than placed in a white box. (Source/wikipedia)

In addition, Green Spine Park also considers the multiple use of public space. In its design, the central corridor of the park is not merely for passage, but a carrier of various functions. Besides serving as a conventional pedestrian path, a running track, and morning exercise field for seniors, the walkway can also become a venue for public activities on different occasions such as festivals and celebrations. Within the park’s management capacity, activities for young people such as skateboarding and roller skating could also be incorporated on both sides of the road. The abovementioned micro spaces along the corridor introduce pedestrian flows from secondary paths.

Three features are considered in spatial terms. The first is ecology, as the botanical garden, rocks, aquatic plants and other elements, are all designed to form a self-balancing ecosystem within a certain area. The second is culture and art that most conventional urban parks lack. The idea is to create a cultural corridor in an unhindered curved form with diverse, multi-scalar programmes, where people are attracted to come repeatedly and eventually become frequent visitors of the park. The third is interaction, which is catalysed through landscape design, the organisation of circulation and use space, and big events such as public science educational activities.(Source/Xuhui Vanke Center)

Safety Issues for A Park

According to the project manager of Green Spine Park, Vanke and the government cooperate in a model of ‘third-party construction and operation’, where Vanke is responsible to build and manage the central green space of the CBD. This is a great challenge for the Shanghai government, in terms of park management, design, maintenance, property security and other aspects. In the grounding of the Green Spine Park project, issues regarding the park’s development, construction and management has also inevitably emerged.

Safety is the primary consideration of park management. For comparison, as for Xujiahui Park, which is also located in Xuhui District, the project manager of Green Spine Park commented frankly: ‘Xujiahui Park has newly opened a 2.02 km greenway, and the number of security guards has increased from 45 to 65. 24-hour access means an increased cost of security, guards and surveillance. Green Spine Park covers an area of about 6.5 hectares. Once completed, it will be the second biggest park in Shanghai CBD, following Xujiahui Park (for comparison: Xujiahui Park 8.6 hectares, Jing'an Park 3.4 hectares, Taipingqiao Park 4.4 hectares). Its expenses in security are bound to increase.’

Another big challenge comes from 24-hour access, which is already a trend of Shanghai's public green space. As of 2017, Shanghai has 43 parks that open 24 hours a day, 365 a year, compared to 22 as of 2016. According to the requirements of the district government, like Xujiahui Park, Xiangyang Park and Caohejing Development Zone Park, Green Spine Park also needs to offer 24-hour access as an urban green space. Opening at night evidently increases its management difficulty. For instance, as for Zhongshan Park, which has not been opened at night until recent years, management issues regarding noise, light, safety and so forth have exposed, underlining its infrastructural inadequacy in its early design phase. Therefore, its cost of human resources, cleaning and greenery maintenance increases by nearly 2.55 million yuan per year. Additionally, Green Spine Park’s adjacency to the Shanghai South Station is another challenge for its management, due to the high mobility of personnel. At present, the daily number of entries/exits of the station is 117, and its daily average passenger flow is more than 50,000 people. As these trains are mostly slow trains that are of relatively cheap fare, for long, there have been safety risks around the station area where illegal employment agencies, unlicensed hostels and restaurants cluster. In the future, the station will become a transit station of the Shanghai Suhu high-speed railway, and its management issues regarding safety will also be given more attention. Above and beyond, safety issues are in fact a common problem faced by urban parks in Shanghai, as many have become where homeless people and tramps gather. For example, the current approach of Xiangyang Park is to persuade them to leave, with the help of urban management officers and policemen when necessary. Similar coordination will be particularly crucial for a park that opens 24 hours.

In terms of safety, the park has to consider and deal with the needs of different visitors, and make particular effort to balance between them. The first important issue concerns the access of non-motor vehicles – are bicycles and shared bikes allowed into to the park? What about electric bikes and unicycles? At present, Shanghai’s comprehensive parks and open green spaces rarely allow bicycles and electric vehicles to enter, mainly out of concerns on pedestrian safety, parking and so on. According to the 2015 amended Regulations on Parks Management in Shanghai Municipality, as well as Shanghai Public Parks Rules For Visitors issued by the Shanghai Landscaping and City Appearance Administrative Bureau in 2018, it is stated that: ‘Except non-motor vehicles designed for physically challenged people, no vehicles are allowed to enter parks without permission.’ Another issue revolves around square dancing. ‘Both Taipingqiao Park in Xintiandi and Xiangyang Park near Huanmao have turn into square dance floors at night,’ said the project manager of Green Spine Park, ‘which means that we must also consider this in spatial terms.’

Moreover, the growing number of visitors with pets also brings new challenges to park management. In its soft opening phase, Green Spine Park restricted pet entry. It will take time to refine the park’s layout and function to allow pets. ‘Similar to their attitude towards non-motor vehicles, almost all parks in Shanghai restrict pets. The main concerns are safety and hygiene.’ The designer of Green Spine Park commented, ‘rejecting pets will fundamentally reduce the park’s attraction. Now that there are more and more pet owners, many people will feel rejecting their pets also means rejecting them.’ To experiment whether pets could be allowed to the park, Pujiang Forest Park that opened in 2017, has started to welcome pets in limited areas during its soft opening. Likewise, in the popular West Bund public green space, plastic bags for cleaning dog faeces are provided to solve hygienic issues. As a third party to undertake management responsibilities of Green Spine Park, Vanke enjoys a certain extend of operational freedom in the management of this urban park. Yet, when coming to more complicated public affairs, this management model is still under trial.

Besides daily management, introducing large-scale public activities has also increased management difficulty. Green Spine Park hopes to present more lively performances with its characteristic outdoor performance space. But they are also limited by weather conditions, especially that Shanghai is rainy in spring and summer. Meanwhile, during the event, management parties including the fire safety department, and public security department are also obliged to intervene. These challenges all require multi-party agreements between the CBD authorities, the neighbourhood, management bodies and governments.

The stepped open space called ‘Wifi Plaza’ that can accommodate 1000 audiences. However, since it is next to residential areas, night performances with noise could not be allowed due to their site condition. This means events are limited to daytime performances of low noise level.(Photo by wei SHEN)

A Park for Whom

For Vanke, building this park is driven by profit. Both sides of Green Spine Park will become commercial centres and office buildings once finished. The park is seen as a strategy to vitalise Xuhui Midtown, a relatively weak area in terms of function and competitiveness within Xuhui District.

‘The Katy Trail in Dallas, U.S. provide a leisure space in the busy city centre, the project becomes a spatial driver of the city. The path stretches 5.6 kilometres along the abandoned railroad track. Even people living in suburbs would go there to run on weekends. Since its opening in 2007, housing prices in the surrounding area have increased, and retail, restaurants, and other businesses have also diversified.(Source/SWA)

But there are also limitations. ‘There are significant preference differences between Chinese and international clients. While the latter, such as PepsiCo, would prefer green space in the community, commercial services and transportation are still the primary consideration for the former.’ Xuhui Vanke Center's property leasing manager emphasised, ‘For example, the ASE Center Plaza in Dapuqiao is a competitor of Xuhui Vanke Center. It has a similar building area, but it has 165 restaurants in its podium, which creates a big advantage.’ Selecting between the green space and commercial convenience, some of the clients have chosen the latter. According to public information, in the first half of 2018, the rent per square metre of the newly built Xuhui Vanke Center office building is about 70% of that of the ASE Center.

This seems to turn the question back to ‘for whom the park is built for?’ On the one hand, the current layout of Green Spine Park can already meet the daily needs of business people working nearby. The operation manager of Xuhui Vanke Center predicted that its tenant companies will be mainly high-tech and internet-related industries, but the office workers will not be frequent users of this park, and they do not have specific needs other than a lunch break. Take the Toutiao news company that entered in 2017 as an example. Their employees are mainly the 'post-90s' generation of young Chinese. Although they value health and fitness, but their interest in urban parks is still unclear. On the other hand, Green Spine Park hopes to attract wider users who would spent more time apart from people working nearby. Its art centre is targeted at young people who would come for activities or exhibitions from all over the city. Other potential users include nuclear families who need places to spend the weekend. To gain their preference, more facilities and services for both parents and children need to be planned and designed. Whether there is space to sit in the park, if there is enough provision of food and drinks, and whether the spaces are shaded in summer, all need to be well-considered.

‘Demand is always elastic.’ said the designer of Green Spine Park regarding the green space’s use, ‘The open space on the west bund of Shanghai is mainly a large lawn with a running track. But it is the lawn that provides space for picnics, yoga, and other weekend activities. That people would come spontaneously and decide the use of the space is what makes the park interesting.’ In the current discussion of urban parks, privatisation and rights to the city is no longer the major discourse; and their role is no longer ‘treating urban diseases’ only. Putting aside planning visions of urban and area development, urban parks still have a long way to go, when parks are no more a picturesque images of certain collective ideals, but spaces for real users.

Acknowledgement: This article is supported by TANG Wen of Wuhan Landscape and Forestry Bureau and Vanke Xuhui Center, Shanghai.

Urban China is cooperated and participated by the Ministry of Construction, Tongji University, Qinghua University, Beijing University, Zhongshan University, Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, Chongqing University, etc. We illustrate urban development from political, economic, social and humane perspectives. Our team is mastered by experts from architecture design and urban planning, and our contents are edited by experienced senior editors with sensitivity to urban development. Our headquarter locates in Shanghai and we use synchronous and co-ordinated editing methods in Shanghai, Guangzhou, Beijing and Chongqing.

Registration information